Seeing then seizing the unseen.

How assumptions can future proof you, your organisation and our society.

We know assumptions can be the mother of all f**k-ups. It's the no-brainer, the obvious thing we should have considered.

But if we look at assumptions another way, they are something else entirely. They are a shortcut to what is known, our conventions, our norms. They are a window into our habits, beliefs and attitudes as individuals and as organisations.

Assumptions are grounded in the past, in what worked before, in what worked then. Challenging our assumptions allows us to peer into the possible, into a potential future.

But when we don't interrogate them, we keep the shackles tied, the blinds down and the road blocked. We miss both the biggest threats and the biggest opportunities. This holds true in our day-to-day lives as well as in the world of business and innovation.

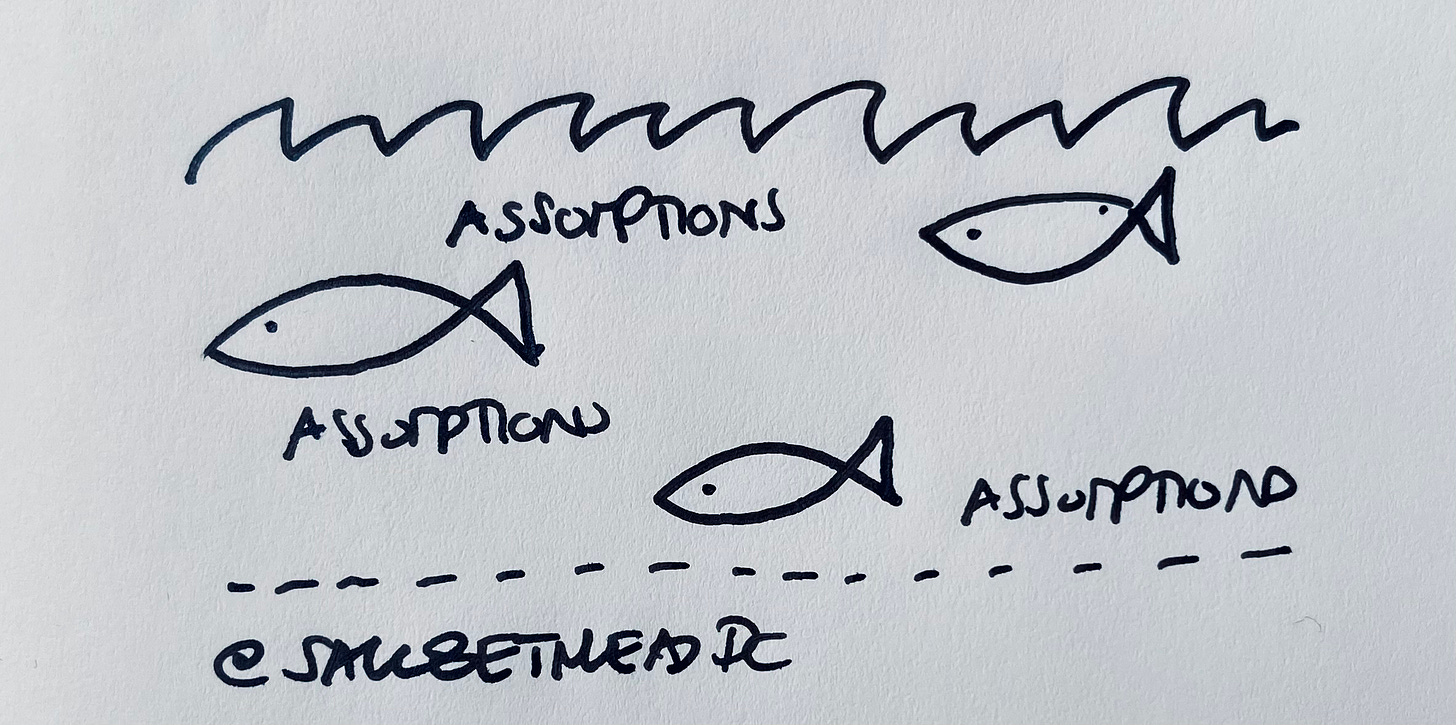

David Foster Wallace's remarkable "This Is Water" commencement speech provides a powerful glimpse into how deeply ingrained our assumptions can be. It begins with a story where an older fish asks two younger fish, "Morning, boys. How is the water?”. The two younger fish swim on for a bit and eventually one of them turns and asks, "What the hell is water?”.

We often don't examine our assumptions because most of the time it's not obvious why we should. Assumptions are the waters in which we swim.

At the centre of this sits another assumption: that things are stable. It's a reasonable one because at any given moment, it's largely true. Even in a given week, quarter, or perhaps a year, it remains true. However, when we zoom out beyond that timeframe, we discover quite how dangerous hidden assumptions can be.

The most striking example is the U.S. Natural Ice Industry in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Advancements in transportation and trade necessitated the storage of perishable goods for longer periods, making refrigeration crucial. What initially began as a way for individual U.S. farmers to keep things cool by storing ice from rivers and lakes in insulated "Ice Houses”, eventually transformed into a global ice industry valued at several hundreds of millions of dollars in today's money. One particular player, The Tudor Ice Company, enjoyed a virtual monopoly. Its founder, Frederic Tudor (aka "The Ice King"), recognised the potential of exporting ice from the cold regions of New England to warmer climates in the Caribbean, Europe and India.

The Tudor Ice Company assumed that the market they were working in was stable. Consequently, they believed that success meant focusing on efficiency: how they extracted, stored and shipped ice, as well as diversifying by finding new markets and supplying ice not only to households but also to industries such as breweries, meatpacking plants and hotels. Their approach involved doing more of the same, but better and in more places.

The Tudor Ice Company possessed enormous resources and deep knowledge about their customers' needs. They had a network perfectly positioned to sense new ways of meeting those needs ahead of their direct competitors. However, they first failed to see, and then adequately embraced a radically new technology that eventually spelled the end of their industry: electric refrigeration and artificial ice.

The decline of the Tudor Ice Company, like many other famous examples of the "success syndrome" (think Kodak and digital photography, or Blockbuster and Netflix), can be traced back to their assumptions about their industry and their understanding of which business they were actually in.

They ended up like a poor lobster, slowly boiling in a pot of their own assumptions.

This is about much more than how organisations succeed in the long run, it’s as true for us as individuals as it is for the organisations we work in and for. Our ability to peer into our assumptions, find where they come from, ask if they are still right and true, couldn’t be more important for our ability to evolve, for our capability to thrive as the world naturally changes around us.

It feels like this can be taken even further: We seem to be going backwards on so many fronts in our world today, appropriately this is often characterised by a great deal of looking back, by a deep sense of nostalgia. A nostalgia born of assumptions about the past and the future, which often grounds us in ‘It was better then’, when we should be asking ‘Is what worked then, what will work now?’. It’s a cycle of assumptions that will never get us out of the mess we seem to be in politically, economically or environmentally.

How can individuals, organisations and societies avoid this fate and embrace this opportunity? It starts by asking different kinds of questions and answering them with an open mind:

What are my deepest assumptions about the world I live in? In my industry, my discipline, my relationships, my community?

What are these assumptions based on and are they still relevant and true? Are there situations where they aren’t? What is it about those situations that makes them different?

Are my assumptions the same as others? If others have different assumptions, what are they based on and are they any more valid than yours?

What if our assumptions are wrong? What will we do differently?

If we view assumptions as dynamic and evolving, see them as a way to embrace the uncertainty and change inherent in life and business, they can be transformed from our biggest threat into one of the most valuable assets we can find.